To the reader: Gnarly Nutrition asked me to write an article about tactics for projecting that could be applied to all sports What follows is my full-length article that is more geared to climbing, a condensed version can be found on Gnarly’s blog.

“Our great mistake is to try to exact from each person virtues which he does not possess, and to neglect the cultivation of those which he has.

Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

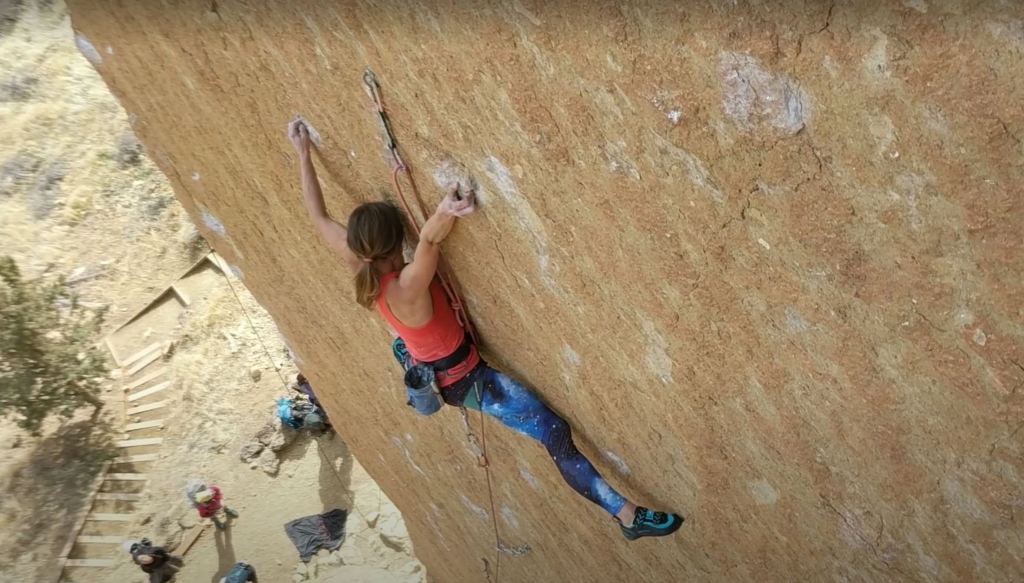

I once existed most beautifully between the moment when I pulled onto a particular rock climb and the moment in which, for the only time, I did not fall off.

It was my first real climbing project and I was enraptured by what it was giving me. The process altered the view of my own possibilities, lengthened the horizon upon which I now gaze.

Still, when the dust of my eventual success settled, my priorities were left in a harsh light for me to examine. Due to my neglect, a good relationship that brought me joy stagnated and ultimately failed. While I nurtured an incredibly enriching and life-long friendship with my climbing partner, I strayed away from others and lost valuable work and life experiences.

It was simple, in the end, to realize that the positive outcome was so rewarding because it was never guaranteed. It’s a rule true in any field — the larger the investment and risk, the greater the payoff. For me, this payoff came in the form of strong and profound feelings of flow, a direct result from how much the route demanded of me. Throughout the process, I discovered great enthusiasm and devotion. In essence, I liked the way it made me climb, and, despite what I later viewed as sacrifices, liked the way it made me live.

Equally, when you strip away the nuances of a sport — of running your fastest, lifting your heaviest, or climbing your hardest — you will be left with what makes a project incredibly difficult, and incredibly special.

When you try, there is always an inherent risk that your aspirations may not align with your abilities or your opportunities. You will, consequently, expose yourself to failure and vulnerability. When it doesn’t work out, the ensuing sting can weave its way straight to your core, a part of which is normally guarded during the pursuit of goals in which success is highly likely.

Though I have never regretted a project, I have become more intelligent about respecting their complexity. Each and every time, I learn that the mental approach I take before I pull onto the wall is as important as the climbing itself.

The advice presented here is geared towards the rarer, large projects which demand a significant investment of time and sacrifice, but are useful for a project of any type.

So, you want to project…

Find the right goal. It should be hard.

Every sport has a metric it uses to denote difficulty. In climbing, consensus opinion is used to determine a route’s grade based on regional classifications.

When a climber wants a project, grade is a natural and immediate consideration for most. This is appropriate, as a grade is our best way of determining difficulty, and difficulty is at the central core of the pure project.

However, it is critical to understand that difficulty is related to but not defined exclusively by any sport’s metric. A hyperfocus on grade will undoubtedly deprive you of valuable experiences and challenges.

Explore your motivation and write it down

If you think you have found a goal, the first steps should occur in the mind, not the body. Ask yourself if your drive is intrinsic — guided by personal inspiration — or extrinsic—– guided by the ego seeking approval or looking to show-off.

There is nothing wrong with saying “I want to climb 5.13a” or “ I want to run a sub 3:00 marathon.” It is ideal, though, if these criteria are not immutable but rather are dynamic, susceptible to change if certain “must-have” attributes of a goal are not met. We all think about and focus on grades, particularly if it is a “benchmark accomplishment” of the sport. Still, consider that you will learn more and be more motivated to stick with the projects in which inspiration is independent of anything but yourself.

When I try to find a climbing project, I have a grade range in which I focus to get me started. Still, my principal concern is with the movement and aesthetics of the route. If neither of those are satisfied, I will move on.

Be unapologetic about what you like, but also consider branching out

I have climbed many 5.13 sport routes, yet I’ve never even tried a 5.12 offwidth or chimney. This is a huge disparity, one which perhaps I should immediately set to rectify.

Yet, I do not have any plans to seek out a 5.12 offwidth because I have never truly wanted to climb a 5.12 offwidth. The time I give to my sport is limited, and I want to use that time to pursue what, for whatever reason, matters to me.

Still, when I showed up to Rifle, CO, an area notorious for a style of climbing I was very poor at, my success on routes felt deeper, because I exposed myself to improving at a weakness. Still, the inherent motivation — the personal desire to climb these routes — was never absent, and thus my motivation was largely intrinsic.

Ask yourself if you are willing to fail

It is reasonable if the answer to this is no. It is not emotionally realistic to constantly make yourself vulnerable to failure. Furthermore, achievable goals will set the foundation for larger, riskier pursuits. Still, the answer to this question will guide your decision making. If you are not willing to fail after a certain measurable metric (time spent trying, number of attempts, etc.), the challenge should be modified.

Ask yourself what you are ready to sacrifice

A big project can feel romantic, a magnum opus of your potential and mastery. In the early stages, sacrifice almost seems like part of the appeal, as if the more you give the more you may receive.

But, weeks later when you take Dramamine so you can work from the car as your partner drives to the cliff at midnight (personally, I don’t recommend this), it feels a little less seductive.

Try to be realistic and predict what it might take to succeed. Can you juggle or not prioritize work? Can you change your diet or other habits? Are you even willing to reduce time given to relationships? Do you have the money to spend on extra gear, coaching, or travel? Are you okay with putting other aspects of your sport aside? The balance between what the goal demands and what you are willing to do will help you determine if now is the time.

Steps to Achieve the Goal

Congratulations, you have found that dreamy project that keeps you up at night and has you eating your broccoli. You are motivated for reasons that feel true to you. Now, it is time for some tactics.

Find support.

Ask what kind of people will build you up

It is incredibly easy for me to get lost in my head during long-term projects, particularly when progress is slow. In these moments, having a partner or a group of people who bring a realistic optimism to the crag — who talk me down from irrational trains of thought and who clearly believe in me —can influence whether I succeed or I fail. I know who these people are, and I go to them for support. Ask yourself what qualities your ideal partner has.

Consider someone for whom you would do the same– whose success on his/her objective matters to you. When it works well, this dynamism can light up both partners to rally for one another, creating an infectious energy. It’s also self-affirming to be with someone who understands your motivation, who you know is driven by a similar passion, around whom you don’t constantly wonder “why am I doing this?”

Sometimes, you might seek a partner with whom you feel comfortable showing multiple facets of your personality to. Projecting can be emotional, and bottling those feelings up may be a hindrance to your mental strength.

Be honest up front to avoid issues later

If you know or even suspect that the support you are asking for might come at the expense of your partner’s own goals, be upfront about it. Unclear objectives or being deliberately coy can jeopardize what could be a mutually enriching experience.Your partner may feel used, breeding resentment and creating tension in the moment of performance. More importantly, this behavior can harm a relationship.

Talk it over with your life partners who may not be involved in your sport, but with whom you spend time often. Be deliberate in your explanation of why the goal matters, and honest if it may come first at temporary expense of your relationship. Never assume that this support is guaranteed or permanent.

Explain how important this is to you, observe how he/she responds and try to strike a chord between empathy and steadfastness.

Then, try to remove yourself from negative or ego-driven atmosphere

Recently, I plopped my rope down in front of a classic 5.13d with a reputation of being very hard. When I came down, it seemed everyone wanted to approach me to tell them about how it was “hard for them” and took them “way more goes than the 5.14b on the left” This felt less like a compassionate warning and more like a strutting maneuver. In the past I was more sensitive to these kinds of comments. Typically, now, I try my absolute best to ignore everyone, with a deference to the criticism and comments of those who actually know me and are familiar with the circumstances and challenges in which I thrive.

Take notes

Every training day or attempt at a goal should be recorded. Simple notes work wonders in jogging memory and in capturing the mental state you were in on a particular day. For multi-season projects, such notes will give you an invaluable leg-up when you return.

During periods of little or negative progress, journaling can be crucial. When I feel like I have a bad day, I often conflate the issue and easily forget about my good performances. Keeping a log allows me to put things into perspective and be accountable to myself. During the truly bad times, my journal provides me closure and serves as a log that I can consult to figure out what may have precipitated the events, or what I did in the past to rectify them.

Finally, if you take note of the small day to day observations that slip into the cracks — how nice the weather was, how motivating it was to see your partner succeed — it can become clear how inadequately you appreciated the moment when you were living it, because your head was focused on the goal. It can train your mind to avoid this in the future and the entire process will be immediately more enjoyable.

Admittedly, it is rare that I re-read my journal. However, the simple act of putting pen to paper can completely shift my mindset on a day, ground my motivation and help solidify my memory for beta and logistics. It is undoubtedly a very rewarding and useful investment of my time.

Focus on the process rather than the outcome

Even if your motivation is intrinsic and not based on external factors , it’s easy to focus on crossing the finish line. Being fixated on the result can not only lead to burn out, but shifts focus to a place in which valuable learning experiences are lost. In fact, I find it is the process of projecting , rather than the end-result, in which I gain the most.

When I went to Washington to try a hard multi-pitch, I was not sure I would succeed. Little of the season was left, and the project was committing in many ways. What compelled me to try was that I was genuinely excited for the opportunity to be exposed to new multi-pitch tactics. I also wanted to explore a potential climbing partnership. I never deluded myself into thinking I did not want to send, but opened myself up to learning and so was extremely attentive in the process, making my days out more complex and meaningful.

Always have mini-goals.

A road map from A to Z without intermediate steps is extremely daunting. Break down the big goal into reasonable, mini-goals and celebrate when you achieve them. Whether it’s a high-point on a route or a personal record on a training run , these accomplishments can go unnoticed without explicit attention, but are very useful in fostering confidence. If you struggle to achieve these small goals, you will realize you bit off much more than you can chew before you are extremely invested. Finally, if you ultimately do not make it to the end, you will have proof of how far you really did come.

Focus on the variables that matter the most.

For any singular goal – rather than a lifelong objective such as “be an all-around rock climber” – you do not have to be good, you simply have to be good enough.

Energy is a finite resource that you should always cherish. Approach a goal strategically and always give yourself the best possible chance at success. Observe what others do and adopt strategies that you capitalize on mental or physical efficiency. Leverage your experience – trust in yourself to do what you do well, and use your time to focus on what you don’t do well.

Have fun, but do not worry if you are not having fun

There will likely come a period in which you are unsure of why you started the journey. This is normal and a large part of why projecting is special — if you do not occasionally go low, the highs will not feel as remarkable .

There is no need to dwell on these moments or walk away immediately. Notice it (take notes!), but continue the hard work. Unless you truly become miserable, refer back to your motivation and let it ground you.

If you regress, reassess.

Extreme fatigue, low-points, or not achieving milestones that were once consistent are all causes to reassess your strategy. When I began to regress on a project early in my climbing, I walked away for a few weeks and climbed easier routes of a different style. Though I was afraid I would lose route-specific fitness, I returned fresh, both physically and mentally.

I was clearly over-training and fatigued. The notes you have been taking thus far will help you figure out the root cause for your regression.

Trust yourself

No one can make a perfect plan, and following an imperfect plan is counterproductive. If your intuition tells you to do something differently, listen. It can be as simple as taking an extra rest day, training harder or completely shifting your strategy. Trust yourself and remember how mixing it up worked for you in the past. Remember, while certain guidelines are typically near universal, sometimes you need to ignore everyone else (including this article) and listen to your gut.

Reflect

Some thrive with a big goal, others find the process overwhelming and not worth the investment of energy. Luckily, we don’t need to truly concern ourselves with why we like or dislike something. You do not need to pursue large goals if you find smaller ones more satisfying. Despite the pressure to project (at least in climbing) the size of the goal does not correlate at all with your abilities.

As for myself, projecting helped defined my relationship with climbing. It helped me learn about what I wanted, and exposed attributes of my personality — both good and bad — I was unaware existed. As a result, I am more confident about my needs and desires, and am more okay with doing less to achieve more. My decision to design my life around climbing was born from these experiences.

Though projecting has shown me what I am capable of doing, it has also made stark how hard I need to work to find success in some of my life-list routes.

I don’t think, though, that the purpose of a lofty aspiration is to later bring yourself down for not achieving it. The distance between what I can do and what I imagine I can do is not suggestive of failure, but rather of potential growth.

Pay attention to the goals or activities where your focus and motivation naturally take your energy, and do them. I have found this to be the absolute best method for success and happiness.

The hard part can be filtering out the noise and figuring out what you want.

Maybe the meaning comes from the process, from the discovery of watching where the energy flows and waiting to see if it returns to light you up, or if it doesn’t.